More Book Excerpts

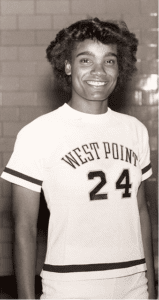

Alma Jo Cobb – Co captain 82-83, 83-84

Cobb was admitted to West Point as part of the Class of 1983, but the academy wasn’t her only option. She had been a strong student and athlete at largely white Bearden High, located in an affluent area of Knoxville. She was one of about 30 Black students among about 1,000 enrolled at the school, she estimated. “Our poor Black neighborhood was zoned for Bearden,” she said. “It was the first high school in the state to have a computer; it had college-prep chemistry and there were kids from other schools who came to take our math and science classes. I was the beneficiary of a West Knoxville education. I don’t know what my older brothers went through with segregation. The people I went to school with were great to me. The teachers were fantastic.”

The support meant a lot to her. “Summing into one brief paragraph all the time, patience, teaching, transportation, food, encouragement, acceptance, confidence and just plain love isn’t enough,” she said, giving a shoutout to her teachers, coaches and classmates at both Bearden junior and senior high schools. “You showed me how to believe in me and changed my life. Thank you.”

Being poor had limited her parents educationally, and Cobb was well aware of their struggles as a result. Her mother, Oneida Jo Hardin Cobb, was valedictorian of her 1945 graduating class at all-Black Austin High School in Knoxville, Cobb said. After high school, her mother began studying to become a nurse but had to drop out after about 1½ years. The program’s cost was beyond her reach despite working a variety of jobs.

She landed a position in a hospital, where she prepared surgical trays and handled other tasks, but was fired in the early 1950s when she became pregnant with Cobb’s oldest brother, John. “It was legal to discriminate this way back then,” Cobb said.

Later, her mother served as a maid for several families and mopped floors at a medical facility at night. “She took me and my younger brother with her sometimes,” Cobb recalled. “I think because we were too young to be left home at night.” The family scraped by. Like other families on a tight budget, her mother bought a pound of hamburger on the weekend and would try to stretch it through the week. The family also ate a lot of hotdogs and other inexpensive foods. At school, Cobb would skip lunch if she didn’t have money to pay for it because she didn’t want to say anything to her parents. She knew they were doing the best they could; their lives were challenging.

Her mom and dad did physical work to make a living most of their adult lives, mirroring childhoods that had been labor intensive as well. Her mother grew up on a farm west of Knoxville, and her father, John Homer Cobb Sr., was the oldest of eight in a sharecropping family in Georgia. He dropped out of school early to work and was largely illiterate. “He could read enough for traffic signs,” Cobb said.

Before her parents were married, her dad served in World War II as a stevedore and repairman. After the war, he felt compelled to leave home after harrowing episodes of violence. “He was being beaten in Georgia by a group of white men,” Cobb said. “The last beating left him on the side of the road — took him days to get home. He didn’t think he would survive another beating.”

He decided to go to Cincinnati where he had family. But he never made it, stopping in Knoxville to pick up some work to help pay for the rest of his trip. The farm work was so good he stayed, and he eventually met Oneida and they married. Later, he became a janitor for the Tennessee Valley Authority, a government-owned electricity provider where he retired after 30 years.

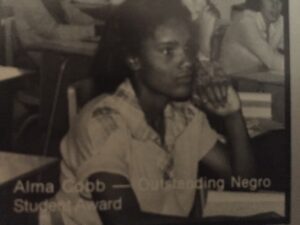

When his only daughter, Alma Jo, was preparing to graduate from high school in 1979, her future looked much brighter than her parents’ had been. West Point wasn’t the only school interested in her; several colleges had reached out. Her hometown college, the University of Tennessee, offered her a scholarship to be part of its women’s track and field team. She also received another scholarship based on her score on the SAT as a Black student. “I had scored very high for a ‘Negro’ — that word is on the certificate,” she said.

Most places in the country, “Negro” had not been accepted language to describe a Black person for about a decade, since the civil rights movement in the 1960s and early 1970s. Yet, under Cobb’s senior picture in her high school yearbook, the caption simply read: “Outstanding Negro Student Award.” Her 680 score on the SAT’s math portion was the key to her score, she said, noting her language arts score was weak.

Most places in the country, “Negro” had not been accepted language to describe a Black person for about a decade, since the civil rights movement in the 1960s and early 1970s. Yet, under Cobb’s senior picture in her high school yearbook, the caption simply read: “Outstanding Negro Student Award.” Her 680 score on the SAT’s math portion was the key to her score, she said, noting her language arts score was weak.

Kim Kawamoto

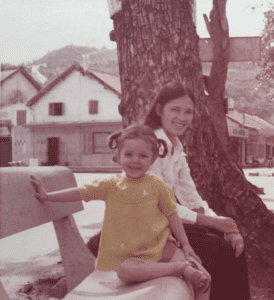

(Kim) Kawamoto (class of 1992) offered diversity in spades, at least from an Asian perspective. Her mother, Nam, was born and grew up in Vietnam on a coastal rice farm, a little less than an hour southeast of Saigon, where U.S. military operations were headquartered during the Vietnam War. When Kawamoto’s mom was a young woman, her parents sent her to the city to earn money, and she got a job selling cigarettes. There, she met the American soldier who would become Kim’s biological father, and in 1970, Kim was born in Biên Hòa, a suburb of Saigon.

(Kim) Kawamoto (class of 1992) offered diversity in spades, at least from an Asian perspective. Her mother, Nam, was born and grew up in Vietnam on a coastal rice farm, a little less than an hour southeast of Saigon, where U.S. military operations were headquartered during the Vietnam War. When Kawamoto’s mom was a young woman, her parents sent her to the city to earn money, and she got a job selling cigarettes. There, she met the American soldier who would become Kim’s biological father, and in 1970, Kim was born in Biên Hòa, a suburb of Saigon.

The U.S. left Vietnam in 1973, and two years later, when Saigon fell to communist forces and was renamed Ho Chi Minh City, Kawamoto and her family departed the country for Hawaii. There, they went to live near the family of the man her mother had met on a blind date and later married before leaving Vietnam, a Japanese American named Earl Kawamoto.

……Kawamoto grew up the oldest of three girls — she has two half-sisters — and became a naturalized American citizen in elementary school. Much to her mother’s consternation and dad’s indifference, she loved sports, especially basketball. “My mom wanted me to study, study, study,” Kawamoto said. “She would ask, ‘How is basketball going to help you — is it going to put food on the table?’ She was the typical Asian tiger mom — she wanted me to be a good student, get good grades and be a doctor.”

……In the summer (1988), she and her dad flew to New York in time to get Kawamoto to Reception Day, better known as R Day, the first day each year for West Point’s incoming class. She was wide-eyed on the trip, having only been to the mainland once, to Disneyland in California. After landing at LaGuardia airport, she saw someone on the ground bleeding in the terminal with police officers all around. She thought about the police shows she’d seen on TV and thought, OK, I’m in New York.

…..Team tryouts were still months away. Like all plebes, she had to get through Cadet Basic Training, a six-week course nicknamed Beast. A few weeks into Beast, when plebes were allowed to call home for the first time, she broke down on the phone because she was so unhappy and wanted to quit. Her mother’s response was not the warm fuzzy blanket she hoped for. “Why are you crying? Are they hitting you?” she recalled her mom saying.

When Kawamoto said no, her mother asked again why she was crying and shared her perspective. “You don’t understand what I came from in Vietnam and then I worked in a hotel,” Kawamoto recounted her mother saying. “I tried to work hard so you can have a better life.” After hearing that, Kawamoto let her mother’s words sink in. “That was kind of the linchpin; I thought, don’t be a jerk,” she remembered.

Coach Maggie Dixon – 2005-06

She (Coach Maggie Dixon) attended a meeting with athletic administrators and team coaches and at the conclusion, athletic director (Kevin) Anderson said to Dixon, “You’re leaving us.” So many schools had been expressing interest in her as a coach — including directly to her and her brother — that the scuttlebutt had a buzz of its own.

“I will never forget what she said to Kevin,” recalled associate athletic director Kim Kawamoto, who was in the meeting. “‘Kevin, I am never leaving West Point.’”

West Point Cemetery regulations called for only West Point graduates and military personnel assigned to the academy and their children and spouses to be allowed burial there. As a civilian Dixon wouldn’t qualify. But it was within Lennox’s power to make an exception. “Her presence is what struck us,” Lennox said in an ESPN feature by Josh Elliott. “That’s the impact a leader can have. In a house of leaders, she stood out.”

West Point Cemetery regulations called for only West Point graduates and military personnel assigned to the academy and their children and spouses to be allowed burial there. As a civilian Dixon wouldn’t qualify. But it was within Lennox’s power to make an exception. “Her presence is what struck us,” Lennox said in an ESPN feature by Josh Elliott. “That’s the impact a leader can have. In a house of leaders, she stood out.”

…..The Dixons decided to accept Lennox’s offer. Her final resting place would be where her head coaching career caught gear. The cemetery was also a national historic landmark, meticulously kept and visited by not only by West Point alums but others who come to the academy. She would be buried among generals, war heroes, military leaders and Army sports stars — names like Gen. Norman Schwarzkopf Jr., Gen. William Westmoreland, Lt. Col. Ed White (the first astronaut to walk in space), Lt. Col. George Custer, Revolutionary War hero Margaret Corbin, football coach Earl Henry “Red” Blaik ’20 and Heisman Trophy winner Glenn Davis ’46.

…..The Dixons decided to accept Lennox’s offer. Her final resting place would be where her head coaching career caught gear. The cemetery was also a national historic landmark, meticulously kept and visited by not only by West Point alums but others who come to the academy. She would be buried among generals, war heroes, military leaders and Army sports stars — names like Gen. Norman Schwarzkopf Jr., Gen. William Westmoreland, Lt. Col. Ed White (the first astronaut to walk in space), Lt. Col. George Custer, Revolutionary War hero Margaret Corbin, football coach Earl Henry “Red” Blaik ’20 and Heisman Trophy winner Glenn Davis ’46.

Under hazy skies, about 500 people attended the burial service for Dixon on Friday, April 14, 2006. The players, in cadet attire of white caps, white shirts and gray slacks, faced each other in two lines. They formed a pathway for the six pallbearers, all Army soldiers, to bring the casket from the silver and gray hearse to the gravesite, located just east of the Old Cadet Chapel.

Preorder The Book

Hoops and Heroes: The Inspiring History of Army West Point Women’s Basketball